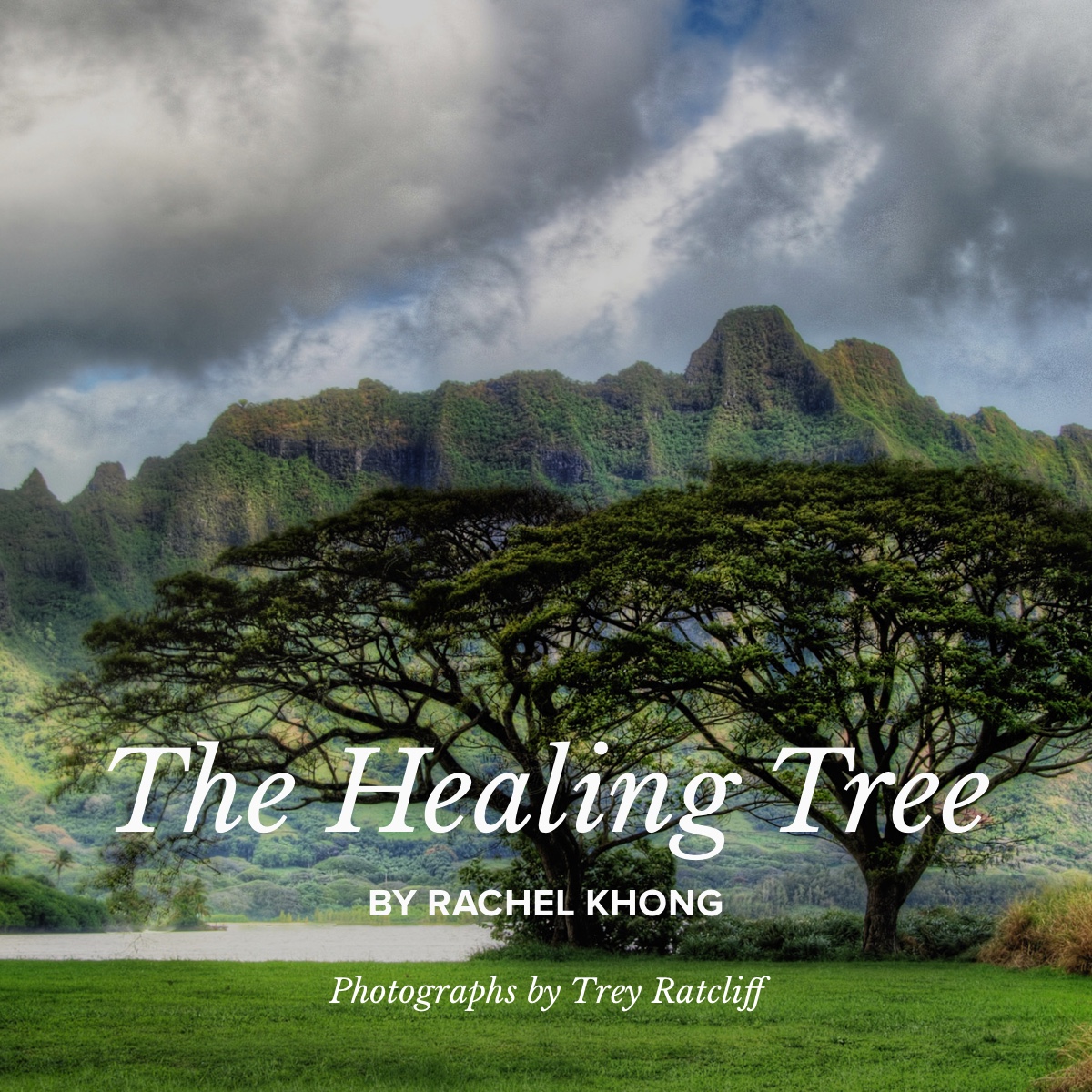

This short story was inspired by Trey Ratcliff’s photographs, part of his “80 Stays Around the World” collaboration with The Ritz-Carlton and taken near The Ritz-Carlton, Kapalua, The Ritz-Carlton, Dove Mountain, and The Ritz-Carlton, Tokyo.

I can’t tell you where I was. I can tell you it was Hawaii—one of the smaller, remoter islands. That’s all I can say. I was on assignment, taking my samples. The tests were standard; they were always the same. They were satisfying to a person like me, who didn’t know basic things, on occasion, like how to be friendly, or how to make someone like me. But I knew plants, and I knew animals, and I knew how to do my work. I’d taken this job, with this company, in large part because it meant I could finally be alone—have an excuse to be alone. I was the fourth of five siblings; I had wanted to be alone all my life, and now I finally was.

I was at home here, in this place that was quiet in the way that expanses of land without people appear quiet, at least at first. If you paid any attention at all, you knew that actually, it could be incredibly loud. The life crept up; then it arrested you.

I smelled it first. It smelled like cool air at the same time it smelled like fresh laundry and honeysuckle and memorable perfume.

What was it that people smelled before a stroke? Burning toast? I wondered if I was having a stroke. I closed my eyes and tried to let the scent guide me to it, but that didn’t help, because the impression was as though it was emanating from everywhere and nowhere. I couldn’t tell if I was walking closer to it, or if I was walking away.

Try harder, I said to myself, I was always saying to myself. So I just walked, trying with all my might not to overthink anything. I walked for two hours, idly swatting the insects away. They’d driven me crazy at first, but I’d grown used to them. They were only trying to live, too.

Finally, I reached a tree. It was huge and looming. I saw that high up in the tree thousands and thousands of flowers shone like chandeliers in the sunlight. The leaves and flowers rustled all together, making a sound like soft bells. A blossom floated down and I caught it; it was the size of my hand and thin and clear as tissue. Somehow it was a pale gold. It smelled like a dream.

The tree’s bark looked smooth and ridged, like a seashell, and iridescent like an oil slick or an insect’s carapace—like it should feel slick or even damp. When I reached out to touch it I found it wasn’t wet at all. Instead it felt warm under my fingers—the temperature of a body, like a living being, and its bark rippled like the surface of water at my touch. I gasped. My heart raced, felt leaden inside me. I touched the tree again and—I know this sounds crazy, but—it seemed to touch me in return.

I had to see what was at the top. Climbing, I lost track of time. I could see the sun setting around me through the thick tangle of leaves and flowers. I felt the air beginning to cool. Despite how high I climbed, the scent never dissipated. Think of the best smell you’ve ever smelled, and multiply it by one hundred, if you can imagine. The birds talked loudly around me, in high chirps, louder and louder as I got higher and higher. When I finally looked around, I realized I was surrounded by them. There were birds in every color. I noticed small birds with yellow heads and green bodies, dark green backs. They couldn’t possibly be Psittirostra psittacea, what the locals called ʻŌʻū, a species of Hawaiian honeycreeper. They couldn’t be because they were extinct, I knew: they had died out in the mid 1980s.

And yet they really looked as though they were, spinning around like goofy ballerinas on their skinny bright pink legs. They flew from branch to branch and over my head. It couldn’t be true, and yet here they were, as real as you or I.

A few more feet, I thought. I’ll just climb a few more feet. I knew I was higher than I should be, but I had to see what was at the top. I put my foot on a solid branch, then shifted my weight onto it; I reached up for a branch to support me. The branch in my hand snapped, and I lost my balance. My heart seemed to stop. I held on to the branch that had been under me. The birds screeched all around me, scattering.

What happened next blew me away: the branch I’d broken healed itself, right before my eyes. It wasn’t anything I could have mistaken for something else. It grew back into its original size. I couldn’t believe it. I broke off another branch, just to see. I watched as the same thing happened, as if on cue.

Right away, I called David, my boss. The company would want to know about this amazing tree, on its own land. In a voice that sounded like I’d seen a magical creature, I told him what I’d seen. He’d never heard me so shaken, nobody had. In all my life, I was measured, calm, but in this moment I was anything but. I gave David the coordinates. He said he would send people to meet me in the morning.

I headed to the Salty Dog, where sometimes I went to drink a glass of their cheapest gin before retiring for the night. It was the only bar in town. It was always men in there, having a loud, good time, and I never engaged, no matter what they said to me. And they always spoke to me, making fun of my silence. There was always one man, who was around my age, who sat there almost every day, drinking what looked like a Shirley Temple—something fizzy with a cherry in it.

Tonight I threw back a glass of gin, quick.

“You’re not from here,” the man looked at me and said, like he’d just deduced this. It wasn’t a question.

“I’m not.” I said this to him with a flat voice—in a way, I hoped, that suggested I didn’t care to talk. Where was I from? I felt more at home here than I did where I grew up, in a suburb of Los Angeles, a fact that embarrassed me. There was nothing ecologically interesting in Los Angeles. I’d fled home the moment I could, at eighteen, and never looked back.

“I’m Sal,” the man said. I’d noticed him here before, always nursing the same drink. He was handsome, I couldn’t help but notice, with dark hair and green-golden eyes.

“What brings you to these parts?” he asked. He sounded genuinely curious.

“Work,” I responded. I held up my hand for another gin and drank it fast, too.

“And what kind of work is that?” he continued, not understanding that I wasn’t interested. Was this flirting? I didn’t do this. I was a person who had only ever been alone, and I wanted things to stay that way.

“He’s a pilot,” the bartender said, trying, perhaps, to be the wing man. I saw this same bartender every day and I’d never bothered to learn his name. I’d watch Sal ask him about his family, about his wife and kids and dog, about what was happening in town.

“I didn’t catch your name,” Sal tried again.

“Helen,” I said, as curtly as I could.

I pushed my empty glass forward and left a big bill for it. A different person would have stayed to talk, but I wasn’t that person.

As David had promised, there was a man waiting for me in the morning. Beneath the shade of the tree, he stood with two other men in hardhats and jumpsuits. I told them what I’d seen, what it could do, and they nodded in a way that seemed unimpressed.

With a chainsaw, they tore through one of the larger branches; little pieces splintered off and flew everywhere. The sound was deafening. The birds flew away. We waited. We watched as that piece grew back in the same way I’d watched it do the first time. The men looked at one another, their eyes widening. But even though the tree healed itself, I watched a patch of its trunk turn blank and gray. I touched that spot and it felt different, unresponsive. They had killed it with their tools; it was dying.

I realized what would happen to this tree, when they dismissed me from its care. They would destroy it.

All my life I hoped I’d do something important, and then I had been completely ordinary.

I knew, in that moment, that I wouldn’t be anymore.

That night I returned to the site. I saw that they’d cordoned off the area with caution tape, which was easy enough to duck under. I took care to cut the branches cleanly and quickly, like I was performing a careful operation. I whispered to the tree, as though it were a child. I’d brought my duffel bag and I filled it with as many branches as I could fit.

Back at the Salty Dog, I found Sal and plunked an envelope full of cash in front him.

“You’re a pilot, right?” I asked.

“Where do you need to go?” he asked.

“Where can you get me?” I asked.

He eyed the stack. It was all the money I could withdraw from my savings account. It was supposed to last me the year.

“California?” he said.

“Not California,” I said.

“Arizona?” he tried.

“Okay.”

“Small planes are the most dangerous,” he told me.

We hardly know each other, and I was trusting him with my life.

I waved the money at him and he pushed my hand back toward me.

When I get you there,” he said. “Then you pay me.”

“When I get you there,” he said. “Then you pay me.”

Sal only had to give it only a moment’s thought, and in that moment I realized how similar we were. Then we were off, up in the air. I watched Hawaii grow smaller and smaller until it was green masses on blue ocean, and then nothing at all—blue and more blue and then finally only the white of the clouds. Once or twice, I caught Sal glancing at me. I wondered what he could possibly have been thinking—if this was the strangest assignment he’d ever gotten. I touched the branches in the bag beside me, and they pulsed with life, though it’s possible, of course, that I imagined that.

I fell asleep. I hadn’t realized how tired I had been. By the time I woke up, we were landing. There was sand all around us, as far as the eye could see—it looked to be blushing, colored coral from the setting sun.

Now I handed Sal the envelope of bills, which he took, almost reluctantly.

“You’ll be okay?” he asked, and I nodded. As always, he looked at me a second longer than he needed to, with curiosity or maybe pity.

He gave me a pat on the back, and then I turned around to walk away. All I had on me was the one bag. It was a hot summer day. I was used to not having much, but this was absurd: a suitcase full of branches, and only the clothes on my back. As I walked away, I had the realization that I didn’t know what I was doing.

I know it sounds crazy but when I looked at my bag of branches they almost seemed impatient. As though they wanted to be put somewhere. As though they were thirsty. I knew that the cacti all around me were themselves full of water, and this gave me an idea: a crazy idea, but an idea nonetheless. I took out one of my branches and broke it. I watched as it healed itself; its powers were still intact. Using my pocket knife, I cut one of the paddles off the cactus that stood before me, and broke another piece of the branch. I pushed the snapped branch against the wounded cactus, with a vague hope that the branch could drink from the cactus.

What actually happened was nothing I could I have ever expected—nothing I had ever seen before, in all my life.

As the branch glowed, making its millions of tiny, intricate repairs, it fused onto its host: the cactus. The branch and the cactus came together and became one. I could have sworn there were sparks.

I was so giddy with excitement that I said yes when Sal asked if he could show me something. He took me to the Blue Lagoon, a geothermal pool outside of Reykjavik, where we were two in a sea of humans. I’d never done anything like that before. That night Sal and I checked into a motel with some of my cash, where there were stains in the carpeting and a smell of smoke in my nonsmoking room. From the motel we could see the northern lights fill the sky outside our window.

He slept over the covers and I slept under. It had been so long since I had looked in a mirror, and when I caught a glimpse I was surprised by who I saw. I hardly recognized her.

In the morning, when we returned, I noticed the glacier was double in size. It had grown leaves, icy discs that made a sound like wind chimes. There was no wind.

Sal flew us to China, to a city in the Sichuan province, a field of bamboo, where we were surrounded by bamboo standing tall and green and straight. It towered above us, endless.

I tied the branch against the bamboo using a scarf, and Sal held it, and we watched as the branch and bamboo fused: the tree branch turned a bright green and then began to grow, stretching endlessly upward. We climbed it. There were carved-in letters from lovers who had walked past this very bamboo. Up high, I saw the oldest inscriptions, still faintly etched: this person loved that person, who loved that person, who loved that person, carved painstakingly, rendered in beautiful Chinese characters.

Everywhere we went I found myself telling Sal more and more about myself, more than I’d shared with a person before. And he told me about his life: how he’d lost his parents at a young age, how he’d lived a lonely life, too.

In Tokyo I held the branch against high-rise buildings, where it fused to the glass and the metal, growing into an almost inorganic shape, jutting upward like it wasn’t living at all. And yet I knew it was. I knew that it had given me life.

What happened, without my really planning it, was that Sal and I fell in love. I don’t know how. We had been travelling, by now, for a year, which became two years, which became five years. Somehow our money never ran out. We flew to Namibia, to Paris, to Kyoto, to Moscow, to Bangkok.

It was the first time I had ever been in love. That was one of the many minor miracles that now made up my life.

In the woods of Northern Idaho, Sal and I grafted our last branch onto a tall fir tree. Like the others, it took without any effort at all. It started to grow upward. All around us, we watched as the forest changed in small ways. Though our fir tree was a lesser version of that first tree I’d encountered, it was more special, because it was my home; all around us was a forest that we’d had a hand in creating. It was a sanctuary for creatures that weren’t home anywhere else, including us. High in the branches, we made a life for ourselves.

Improbably, Sal and I grew old together. I know that never happens anymore, I know that things get complicated. But we made each other happy, so it happened, somehow, to us. And the last part of the story goes like this: one day, while Sal was reading the paper, I ventured outside. We had built our home high in the trees, and our children lived next door, and their children too. The branches had grown and grown; they spanned miles.

I took one branch—we called each big branch a road—past my daughter’s house, past my granddaughter’s school, past the ice cream shop that served one hundred flavors. I walked and I kept walking; I had never realized how far the branches had grown and I wanted to know. I’d always loved to walk and so I did. I walked, for weeks, from Idaho to Chicago to New York and everyone seemed to know my name. And after I had walked for weeks and then months and then years I was back where I started from, and Sal sat there, looking annoyed, in the way that people who love you sometimes look annoyed when you are gone a long time.